Walking In Their Boots: (Dis)Respectful Representations In Arthouse Cinema

French filmmaker Julian Schnabel enters the art-world smashing plates in one hand, using the ceramic rubble to canvas large-scale paintings with the other. His works are textural, rugged, multimedium; often so large and dimensional they begin to blur the line between sculpture and painting. Using everything from ceramics to antlers to velvet to surfboards, his reception in the American art-scene lended towards the wild and brash expressibility of his pieces more so than their critical success. One particularly flourishing critique penned that "Schnabel’s work is to painting what Stallone is to acting: a lurching display of oily pectorals".

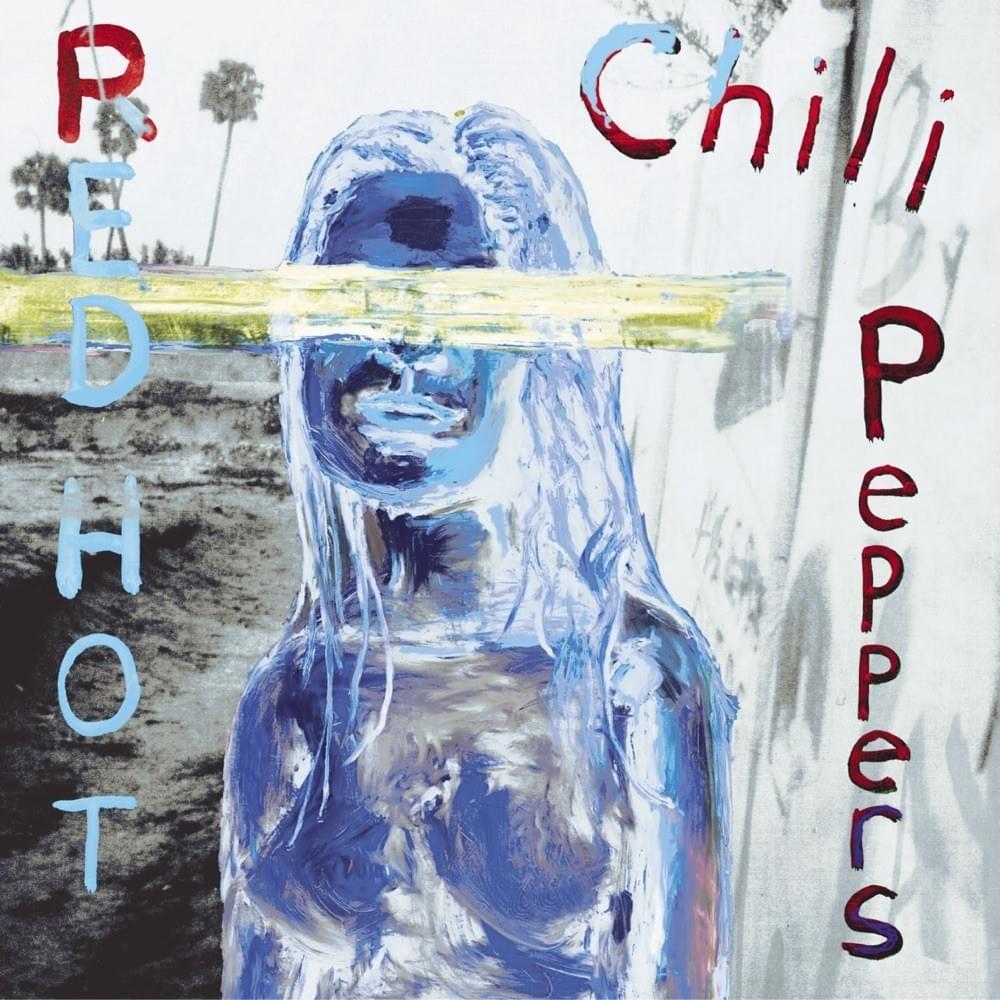

His daughter Stella Schnabel was at this point dating a member of the Red Hot Chili Peppers. In curiosity, lead guitarist John Frusciante sends home with her one evening some rough demos of By The Way to pass on to her father. He listens, he enjoys, he ‘gets the vibe’. Julian Schnabel goes on to produce the cover artwork for the album. Yes, the topless woman depicted is his daughter.

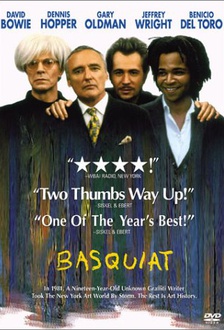

With this, Schnabel seamlessly glides from ceramic sculptures to nude family-portrait album artwork to arthouse film. Considered to be one of the first commercial films about a painter, by a painter, Basquiat emerged in 1996 to the reception of both fame and fury. While it made international waves in the box-office, behind drawn curtains both art and film communities were incensed. Many critics ended up attacking Schnabel’s character; both as a person and in his confusing attempt to insert himself, via Gary Oldman, as a character in the film.

The mentality Schnabel approached Basquiat with was that even though he had no relationship with Basquiat personally, he knew what it was like "to be attacked as an artist … judged as an artist … to arrive as an artist and have fame and notoriety. I know what it’s like to be described as a piece of hype … to be appreciated as well as degraded". It was however this exact mindset that critics picked holes in; that Schnabel assumed he could fit, as a filmmaker, inside the shoes and mind of Basquiat.

A shared positionality of ‘the artist’ who circulated in likeminded circles was not, neither then nor now, enough to procure the intimacy and empathy necessary to respectfully portray a life so disparate from Schnabel’s own. Considering The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (2007), a later film of Schnabel’s with fewer racial implications, it is clear his eye was in dealing with the complexities of the artist in suffering. No doubt he was comfortable representing the image of the tortured artist, but perhaps not an artist’s interaction with their entire world and social stratification. Furthermore appreciating Schnabel’s prior experience as a painter and not as a filmmaker, perhaps his intent and passion in film strayed more towards creating an art piece, not an essay on art history and culture. In both Before Night Falls (2000), The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (2007), and At Eternity’s Gate (2019), Schnabel maintained an intense intrigue in the portrayal of artists in turmoil as executed through the lens of arthouse cinematography.

Though it made for a vibrant and neoexpressionist filmography, in the case of Basquiat this personal and experimental reimagining of another’s story through Schnabel’s own experiences in the art world was one that ultimately whitewashed and disconnected Basquiat’s life and experiences from a more authentic presentation. With scant mentioning of Basquiat’s heritage or his relationship to black history and culture, it is possible that Schnabel’s positionality led him to leave the subject untouched. Perhaps feeling entirely out of his depth in credibly portraying this part of Basquiat’s whole, the elephant in the room makes eyes not only at Schnabel but at the wider arts community - are we allowed to pick facets of a person’s life to depict depending on what we know, and what we are comfortable with?

This morally murky trail I followed through Schnabel’s entire filmography led to an appreciation that it is certainly not only Schnabel who fell down the rabbit-hole of confusing artistic recreation and entertainment with revisionist appropriation. In his many attempts to create his own artworks out of protagonists Basquiat, Jean-Michelle Bauby (The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, 2007),and Reinaldo Arenas (Before Night Falls, 2000), Schnabel’s process and medium inevitably diminished, characterised and fictionalised. While respect and admiration can be payed to Schnabel’s contribution in platforming the stories of artists to commercial and international fame, it is undeniably Schnabel’s Basquiat, Bauby, and Arenas we are platforming.

Many directors or fellow artists will meet Schnabel at this quagmire of understanding the ethical tightrope between artistic recreation and respectful portrayal. A useful way forward has been provided by more ethnographically focused documentaries, whose culturally sensitive content has often inspired and forefronted a hefty tome of political and ethical discourse on how another human is portrayed through an individual or collective lens. From decades of ‘anthropological’ cinema that teetered towards more uninvited observation than consensual sharing of knowledge, ethnographic filmmakers have now set out for them ethical principles to ensure communities being filmed have input into how they are portrayed.

This is an approach for filmmakers perhaps not only applicable at a community level, but also on an individual level. Schnabel was unfortunately oblivious to the social cues of Basquiat’s estate denying any of his art to be used in the film, Basquiat himself purportedly not even liking Schnabel as a person, or Jim Jarmusch coming out to state he would never watch the film because he "knew Jean-Michel and he was not friends with Julian … I refused to talk to Schnabel about Jean-Michel when he was making the film … Jean-Michel was not a fan of Schnabel as a person back then. And I would not betray him in that way." Likewise in The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, close friends and family came out after the film enraged by the alteration of events that depicted characters in negative lights with no justification from Schnabel; a former lover of Jean-Michelle Bauby went so far as to put out her own work, The False Widow, documenting her own perspective in response to the misinterpretation.

This film was not a story of Bauby, but a story for Hollywood. Not a picture of Basquiat, Arenas, and Van Gogh but a different canvas entirely; one that when you zoom out far enough, seems to be more a large-scale self-portrait of Schnabel. Where are we, the mere and meek audience member, left in this quarrel? Can we sit with knowing that it is only Schnabel’s story we are really watching? If the conversation of consent will be cropping up on our cinema screens for a while yet, a continuously critical eye and acknowledgment of positionality in both cast, crew, and viewer, is perhaps the first lens we can give our screens.

Xan Coppinger hosts the Sound and Vision segment on The Breakfast Spread each Tuesday at 8am, as well as co-hosting Solaris every Sunday at midnight alongside Clancy Balen.